Traveling to North Korea this past August was an exercise in double vision. I saw the carefully constructed narrative that the government wants outsiders to see, but having missed out on a lifetime of government-sponsored conditioning, I was naturally skeptical. While I make no pretense to know all the nuances of the North Korean situation, the time I spent there gave me some insight, however limited, to life on the ground. While there, I began to understand the impact of state-imposed isolation and I wondered, how much longer can the government sustain this carefully crafted myth that life in North Korea is normal?

When I left the airport I found that I was but an audience to an intricate performance dedicated to assuring me that life in North Korea is productive, peaceful, and satisfactory. But when life has to be directed, rehearsed, and performed day after day, it’s not normal—it’s spectacle. I felt like I was on the set of The Truman Show, but instead of the pastels of the artificial Florida paradise created and maintained for Truman and his loyal audience, the set for the North Korea show is dominated by walls of concrete that, from a distance, look well maintained, but up close, the signs of deterioration betray the state’s narrative of the success of self-reliance. An eerie silence reverberates off the concrete, a silence born of isolation. Even though I was in the capital city, there was a distinctive absence of the usual urban activity. It was two days before I saw my first car on the streets of North Korea. It’s jarring to be in the midst of an urban setting and experience this silence—a silence that signals deprivation rather than choice.

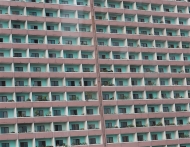

While in Pyongyang, the capital, I stayed at Yanggakdo Hotel, a hotel reserved for foreigners only, set on an island, allowing foreigner guests little to no access to North Koreans who haven’t been screened and officially approved for contact with Westerners. The hotel was bare bones but still something on the extravagant side in North Korea. Just like the communist construction of the Soviet Union, the buildings in Pyongyang lack character and design elements that individualize—the architecture is one that speaks to the effort of the masses rather than the vision of an individual

My contact with North Koreans was limited to the people in this foreigner-only hotel, my tour guides, and people on officially-approved stops. This limited contact left me an observer of life far removed, staged at a distance. Touring, I saw no obvious signs of commerce—no storefronts, restaurants, or shops. My tour group did pass by a small market, but the size of the market left little doubt about the scarcity of food. When I did see food for sale, it was rotting.

A constant state of fear is a reality in the lives of North Koreans. So much so that the government actually plays lullaby music over loudspeakers throughout the city late at night through the early morning hours in what seemed to me an effort to soothe and calm the citizens—an effort that struck me as absurd. In a city with no sounds of life, no birds, no dogs barking, no people laughing or having an argument or living out loud in any way, the state-sponsored lullabies had just the opposite effect; rather than calming me, the music woke me up to the realities of life in North Korea.

In addition to the nightly lullabies, the government also sponsors an annual festival to celebrate North Korean culture and to deify the leaders of North Korea. The Arirang Festival honors the birthday of Kim Jong Il and runs from August to October. The Mass Games, an important part of the festival, are live performances celebrating the Workers Party of North Korea, Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, and the strength of North Korea’s armed services. Heavy with symbolism, the Mass Games feature highly trained performers—100,000 children ages 5 to 18, who have been plucked from the outlying districts to take part in the Mass Games. Not to push the Hollywood references, but one of my traveling companions said it reminded him of The Hunger Games minus the brutal kill-or-be-killed storyline. I sensed that being chosen for the Mass Games was an honor, and one that brought with it food, shelter, and possibly a career to children who may not have been assured a regular meal, a place to sleep, or a secure future.

On a tour of a “typical” North Korean home, I quickly realized the home was also staged as there were no signs of the home being lived in. Rather than a typical home, it looked to us like a something out of a museum, a space on display with no signs of the realities of every day living. There were dishes on display, bearing no evidence of ever having been used and the kitchen showed no sign of being lived in. The home was supposed to show us the quality of life in North Korea, but all I saw was the effort that went into maintaining the fiction.

With so much of what I saw seeming scripted, it was a relief when I saw events that seemed authentic and organic. While waiting for a train, I noticed two children playing in the station. The seemed to forget themselves, without a worry about who was watching or what others were thinking. They were so involved in their games they nearly missed their train and only barely caught it, running to get in the car before the doors closed. It was the sort of scene I would have taken for granted in a Western city, but here I had seen so little spontaneous behavior, it struck me that the children’s behavior grew out of an innate sense of freedom. For a moment, there were just two kids playing. The next moment, they were gone.

Perhaps rightly enough, it was children who gave me a sense of hope for this country’s future. While waiting at a monument, I sat down and looked out towards the street and saw a group of Korean school children, walking in a pack. When they spontaneously broke out in song, they seemed light at heart. As the children sang their way down the street, I felt my spirits lift. I waved to them. They laughed and sang a little louder. A simple gesture, a simple moment of spontaneity, and I felt the burden of the carefully constructed narrative dissolve. To be sure, it was not act of dissent, rather it was an act free of any sense of the script. These children were not performing, they were being kids—and finally, that felt normal.

Exhibition Dates: June 1 – October 1, 2013

SFP Studio - Sun Valley, ID