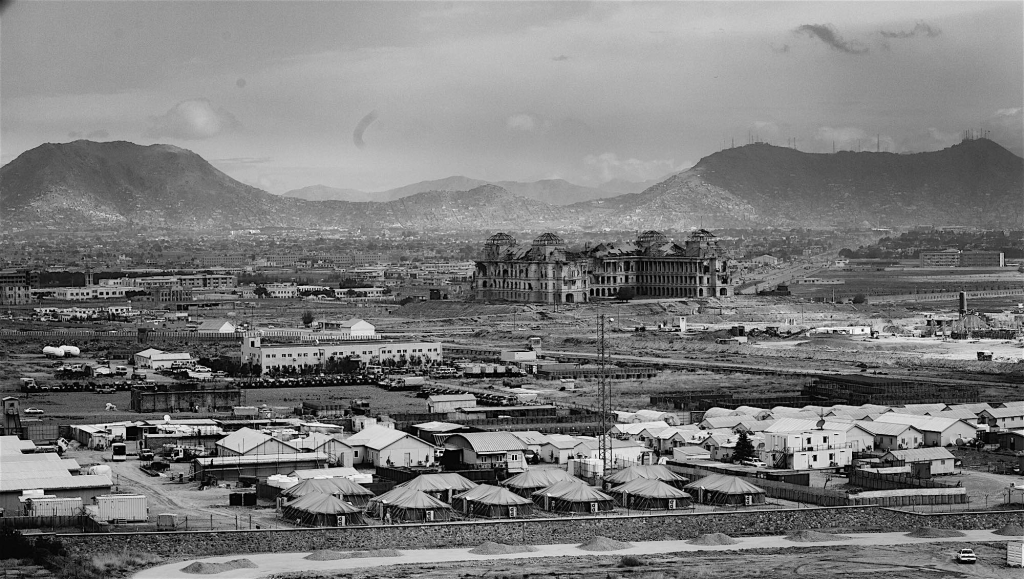

72 Hrs Kabul

16x20

$$1,000

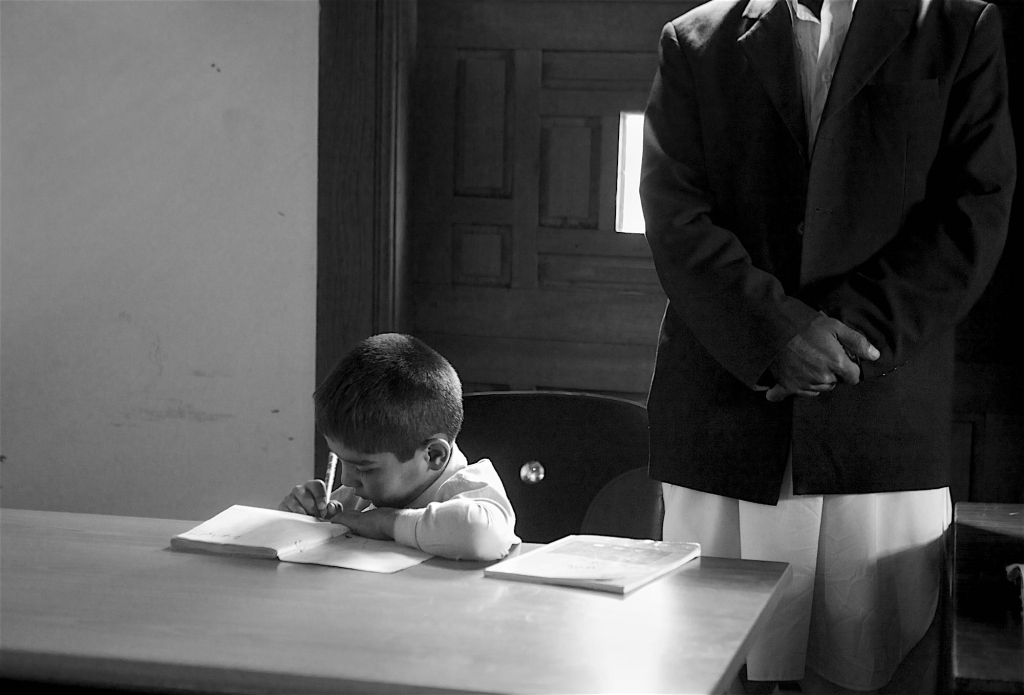

Rule of Law

11x14

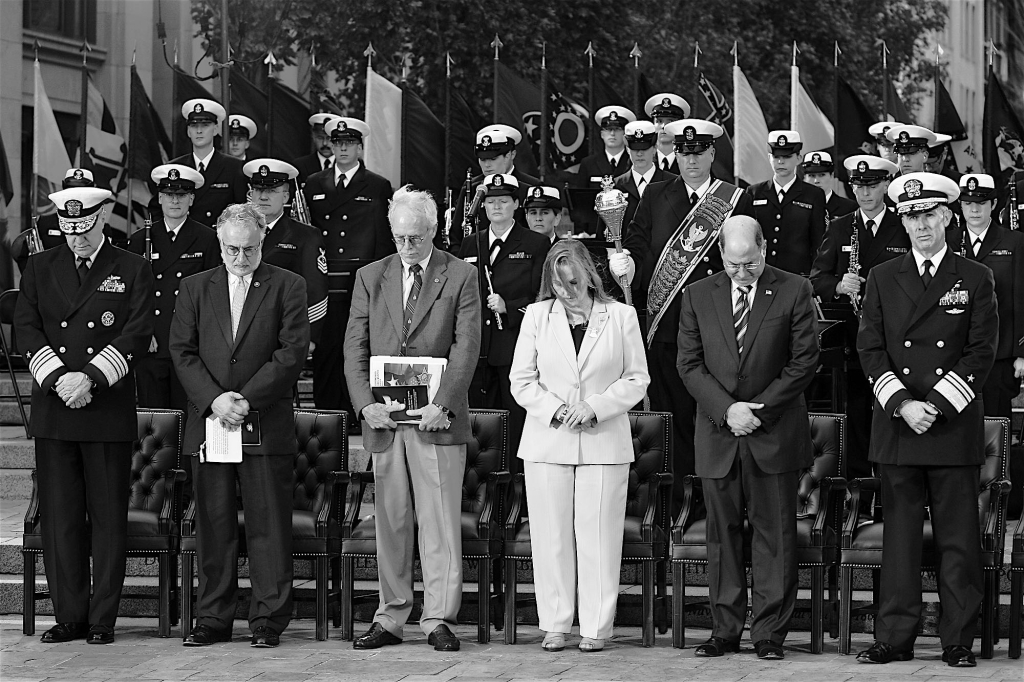

Medal of Honor

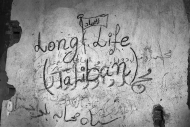

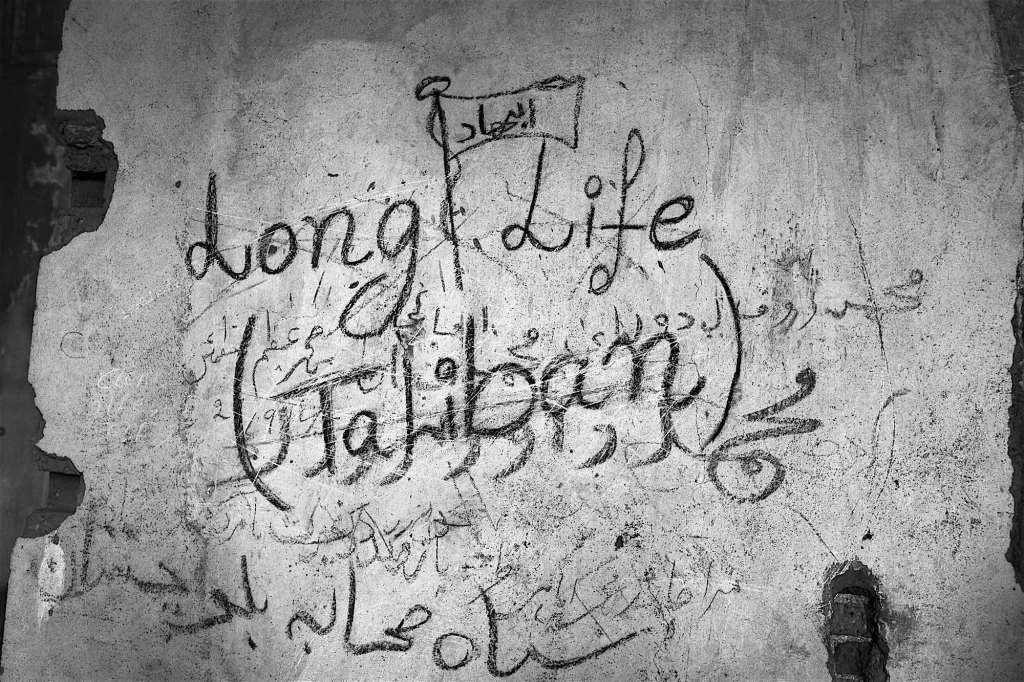

On September 11th, 2001, the shape of the world changed for Americans. The sense of security that grew with decades of peace and prosperity was shattered on a beautiful morning in America. For the first time since Pearl Harbor, America was attacked on its own soil. Suddenly the wider world shrank and Afghanistan became America’s major national security concern. We went to war in Afghanistan because the country had long provided safe haven to terrorist groups. “Al Qaeda” and “Taliban” became household names.

Afghanistan is a country of tribes. Tribal identification trumps national identification and that is one of the many complexities of this country that makes it impossible to understand. There are entire generations in Afghanistan who know nothing but war. Entire lives have been lived to the soundtrack of bullets and bombs. There are generations of men who have lived lives of quiet desperation while they watched foreign invaders knock down their doors and take their brothers in the middle of the night. And there are men who stood by as they watched the Taliban enforce a brutal and inhumane rule on their neighbors. There are scores of women who once knew what freedom tasted like, but for years had to live under a veil of silence, enforced ignorance, and servitude. Generations only know a country invaded by outsiders and that breeds distrust and anger. When we try to understand life in Afghanistan, we have a hard time understanding what it is like to live in constant war. This isn’t to excuse the violence that has gripped Afghanistan for generations; it’s just an observation about life in the midst of war.

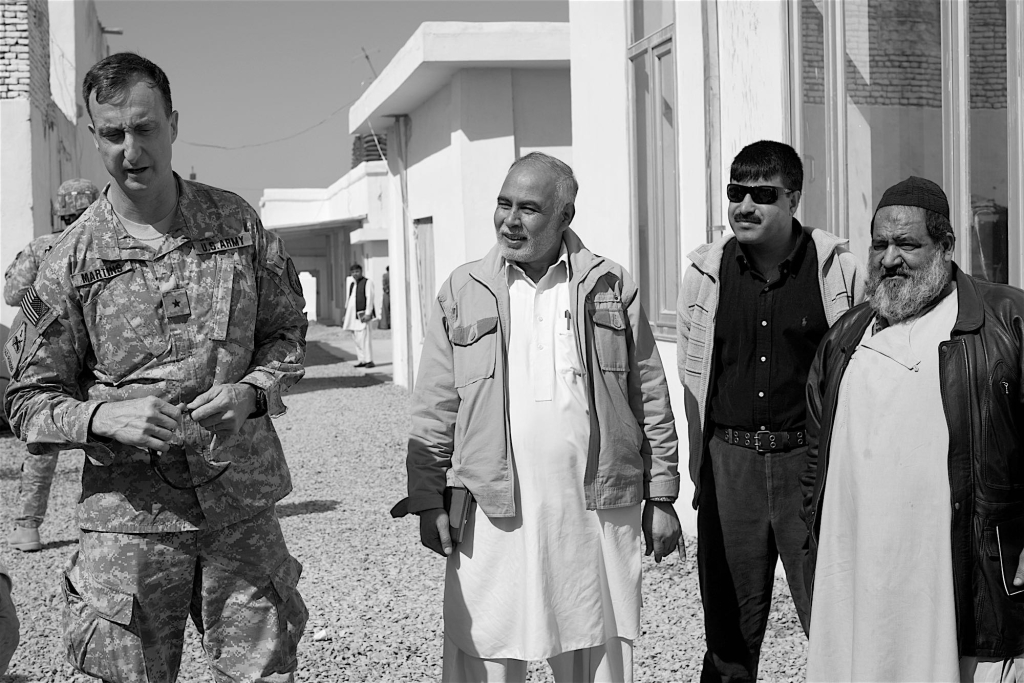

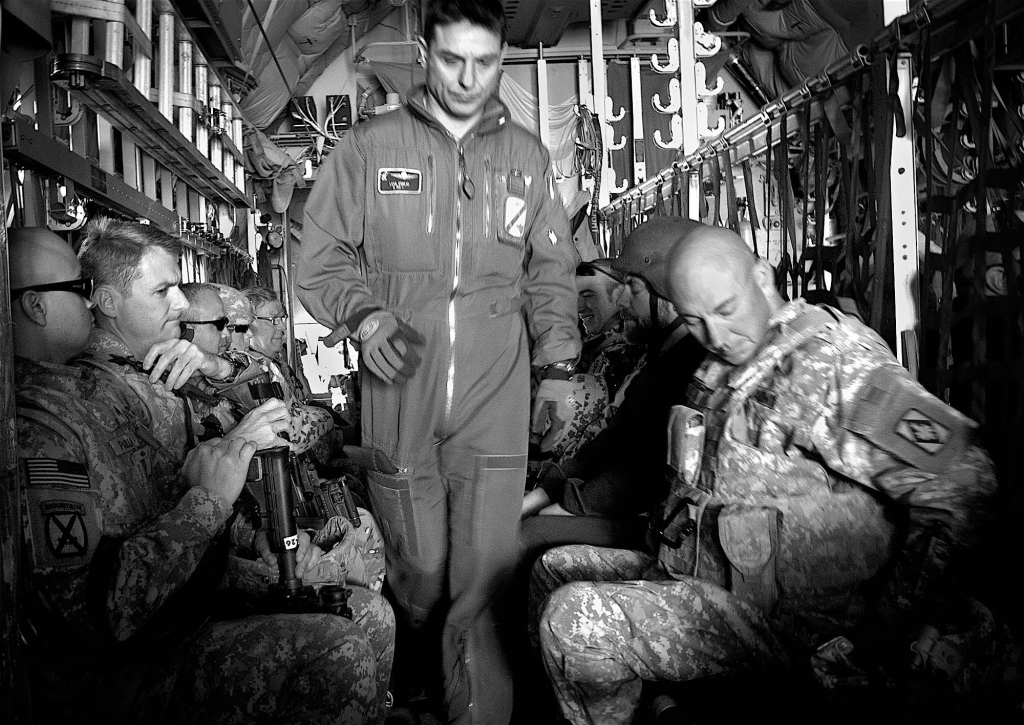

It’s 2011 and we’ve been at war for 10 years in a country that did not attack us. As I sat in a Blackhawk helicopter flying from Kabul to Khost during my last trip to Afghanistan, I was plagued by questions. I needed to get on the ground and witness life in Afghanistan to understand what this 10-year war has been about and why Afghanistan had become a safe haven for terrorists. I realized that those questions aren’t for me to ask or answer; I was in Afghanistan to document a country in the midst of a rebirth. I was there to document the war and the peace at the root of such a rebirth.

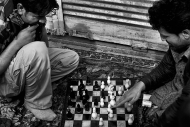

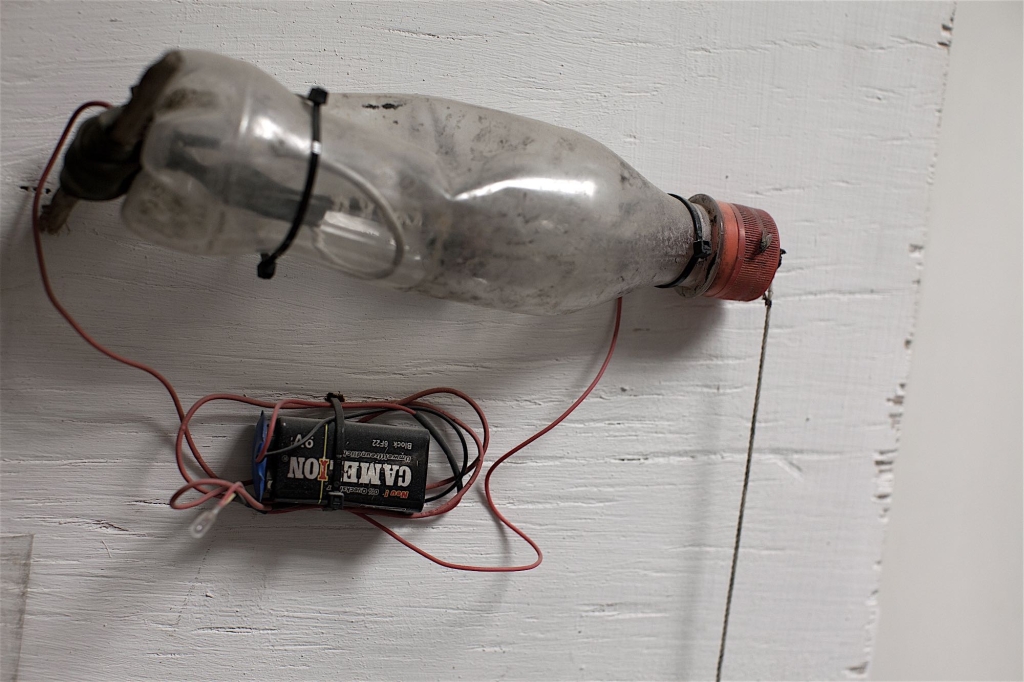

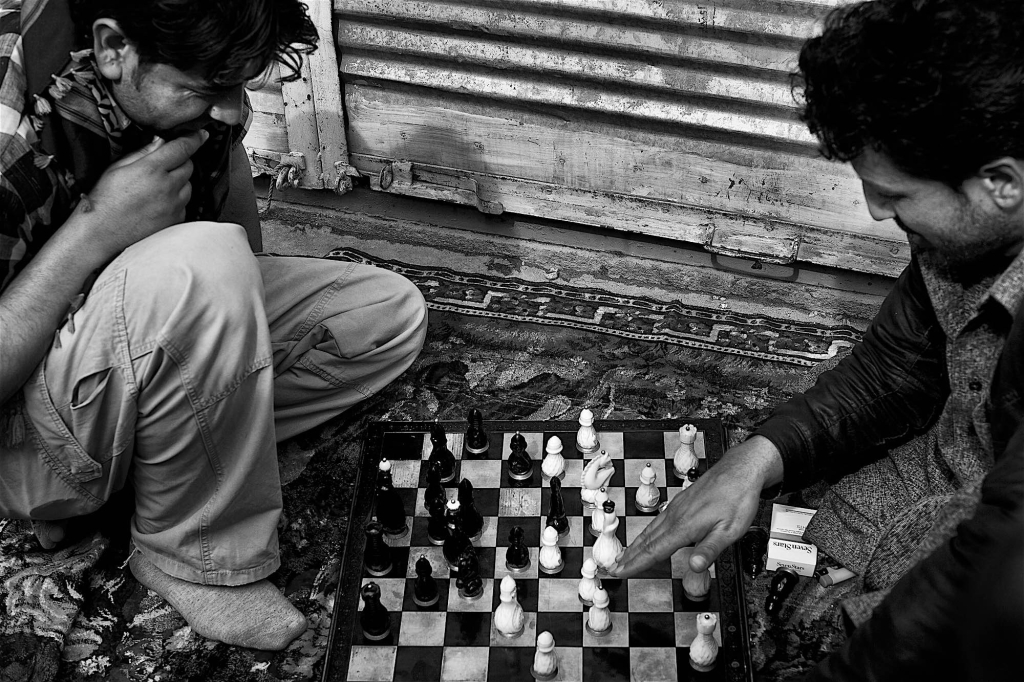

It’s easy to say what war looks like; we have photographs, videos, first-hand accounts—but what does peace look like in the midst of war? Everywhere I looked in Afghanistan, there were moments that told a story and that story offered brief hints of peace: there’s a woman shrouded in the azure of a burka walking down the road passing a soldier shrouded in the camouflage of his military garb, both isolated by their ideas of the other—but they pass, without incident, and that’s peace; there’s a group of women, multiple generations, watching over their children as they play on the rooftop. I wanted to know the weight of their conversation because the fact they had carved out a few minutes to participate in this ritual of women conversing, that’s peace. The tailor working in his shop, isolated yet open for business, doing what he loves—that’s peace. It’s the small, everyday moments that miraculously take shape in the midst of the bullets and bombs. These are moments we might not recognize in a place protected from the realities of war because they are so commonplace. But here, in Afghanistan where entire generations have known nothing but war, peace should be documented, recognized, and honored.

As I consider the cost of this war, in terms of the lives lost or shattered, I cannot help but wonder who is accountable for all of this? We went to war with an idea that can’t be bound to a geographic location. It’s an idea worth fighting—terror—but I can’t help but think, who is accountable for the lives we’ve lost, and who is accountable for the money we’ve spent on a war we cannot win? Who will stand up and take responsibility? At long last, when someone does, maybe we can begin to heal and maybe then, peace will take root in Afghanistan.

Exhibition Dates: September 8 – December 1, 2011

SFP Studio - Sun Valley, ID

72 Hrs Kabul

16x20

$$1,000

Rule of Law

11x14

Medal of Honor