Women Vets

Having spent over a decade working in the U.S. Navy SEAL community, I have seen first-hand the impact that combat can have on our soldiers and their families. As more women veterans began to come back from Iraq and Afghanistan with traumatic brain injuries (TBI), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and military sexual trauma (MST), I wanted to honor their service by documenting the battle they now faced—life after war.

What I learned was that women vets were returning home from war and having real struggles coming to terms with life after war and finding a way to fit back into the day-to-day of their lives with family, friends, and jobs. Studies have shown that women veterans who return with TBI, PTSD, and MST have a harder time than their male counterparts keeping their domestic life on track—more marriages end in divorce and more women vets end up facing financial troubles and even homelessness than male vets. While men too struggle with coming home, as a culture, we’re better and more accustomed to supporting men as they come home. But military’s health care options do not serve these women well. Only a small fraction of the nation’s VA hospitals provide comprehensive health care for women and female staff members are so rare that only seven percent of women veterans can see a female therapist. Many women vets will forego therapy rather than seek treatment for their MST from a male therapist. So, countless women go untreated.

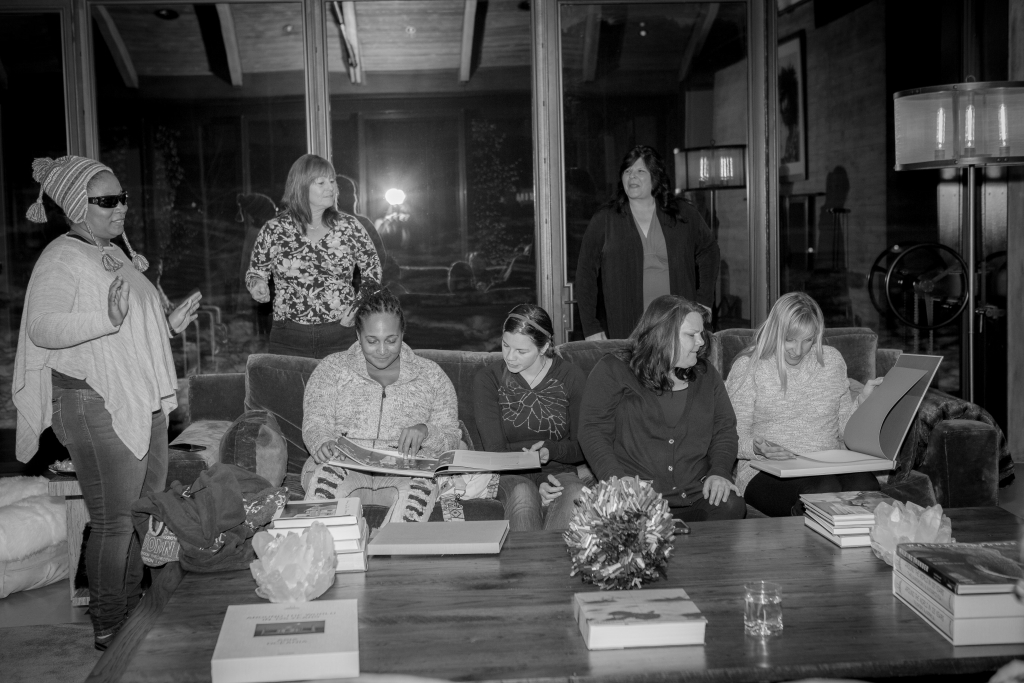

Sun Valley, Idaho’s Higher Ground organization is dedicated to helping veterans with TBI, PTSD, or MST through introducing them to outdoor recreation, engaging them in group sessions where they share their stories and help each other heal, and offering them a three-year follow-up program where Higher Ground will help veterans participate in outdoor recreation as a way to recover. I spent time with many of their women-specific camps, photographing the vets as they got to know one another, told their stories, and found ways to expand their comfort zones through play and sport. But more than anything, I witnessed these women learn to trust again—even if it was only a small window of trust, it was enough for these women to build on as they went back to their lives. That trust—trusting others, trusting themselves—is central to their ability to heal.

I was drawn to working with the women vet camps because I saw females—mothers most of them—who were called to serve their county, and in doing so sacrificed a part of themselves when they left their families behind. I met women who fought for the right to serve their country and returned from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wounded psychologically as well as physically. Women who had been raped by peers or commanders and now find it hard to leave the house, hold down a job, or trust anyone in their lives. Women who had been on guard at the base when an explosive device sent them flying into a trailer leaving them with brain injuries. And every woman I met mourned the loss of who she was before she left to serve—her independence as much as anything.

Higher Ground works to restore that independence as well as dignity. A core component of the program (for both the men’s and women’s camps) is that each vet brings a support person (a spouse, sibling, friend, parent) because they will surely need support but their support person will also need to connect with others. Their supporters can help them identify and understand their triggers and help them cope with those triggers. The community that Higher Ground builds for these women and their supporters lasts and is an important part of the healing. In working with Higher Ground I saw an organization vital to the reintegration of these brave soldiers, men and women, and I saw women learning to adjust to their “new realities” and finding ways to not only cope, but to thrive again.

Women Vets